2020 is supposed to be the year where we really have to turbocharge the green transition. However since the early spring everything has been characterized by a completely different agenda. The corona virus has hit the global economy and the modern societies where we are most vulnerable: Accelerated infection rates, death rates—and not least unemployment rates—speak their all-too-clear language around the world.

We people on the Danish west coast can console ourselves with the fact that we certainly do not live in the most exposed part of the world: The social order in Denmark is extremely strong, we are well disciplined, and we have collectively proven our ability to act together and resolutely. Regardless of the fact that the corona crisis will undoubtedly affect our world for several years to come, everyday life in most places in Denmark has long since returned to something resembling normality.

Nevertheless, we should of course see the covid-19 pandemic as a wakeup call: a welcome opportunity to reconsider why we live and dispose of our time as we do.

Just a few days after the shutdown of Denmark, you could measure how the air quality in the larger cities had significantly improved.

The corona crisis has not made either the problem of global warming, or the need for a thorough, green transition any less relevant. On the other hand, the meltdown of the labor market has clearly demonstrated how directly our modern market economy affects the nature around us: Just a few days after the shutdown of Denmark, you could measure how the air quality in the larger cities had significantly improved.

We live in a rich and privileged society and have had every opportunity to get the economy back in gear and get back on our feet. But the question is whether it is not precisely in times like these, when the state is pumping unheard-of massive investments into the economy we also have a damned duty to think new? The question is whether it is not now, while the crisis is still fresh in our minds, that we must lay the foundations for a different green and sustainable economy?

It is obvious to initiate the aid packages that are still necessary to support certain sectors, so that they act as a giant carrot to promote sustainable business. At the same time, we must show the necessary courage to swing the stick, and tax fossil energy, to an extent where it really does (and moves) something. As the Danish climate council Klimarådet have shown, there is no way around the unpleasantness if we really want to live up to our own ambitious 70% reduction targets.

Let us therefore stand together in the slipstream of the corona crisis and draw the contours of a green economy, where local food and services—and generally things that are created locally—are relatively cheaper, and thus competitive. Even if each single one of us end up with less money in our hands, our real, experienced purchasing power will still be formidable.

Imagine that picking the North Sea prawns in Morocco, just to drive them back to Northern Europe is as expensive and difficult as it sounds absurd and that our livestock must live on local crops, because the idea of clearing rainforests in South America and shipping the soy halfway around the Earth is as expensive as it is against every principle of sustainability.

I personally dream of small, well-organized local communities the size of villages, with everything from blacksmiths and butchers to nurses and caregivers—and not least the indispensable dreamer and madman; an everyday life, and a world where we don't have to move either ourselves or our goods over crazy distances and have time to grow our vegetables, take care of our livestock, and teach our children to learn about the world; maybe go hunting, or do some fishing in the fjord. Think Dunbars number and consider for a moment how it can be done:

Imagine an urban space, arranged on the premises of our children and not of cars or property developers and mortgages: Green recreational areas, with plants, insects and life where there are otherwise just roads, asphalt and concrete; winding waterways, cycle paths and trails. The electric trains and the remaining autostradas as far underground as possible.

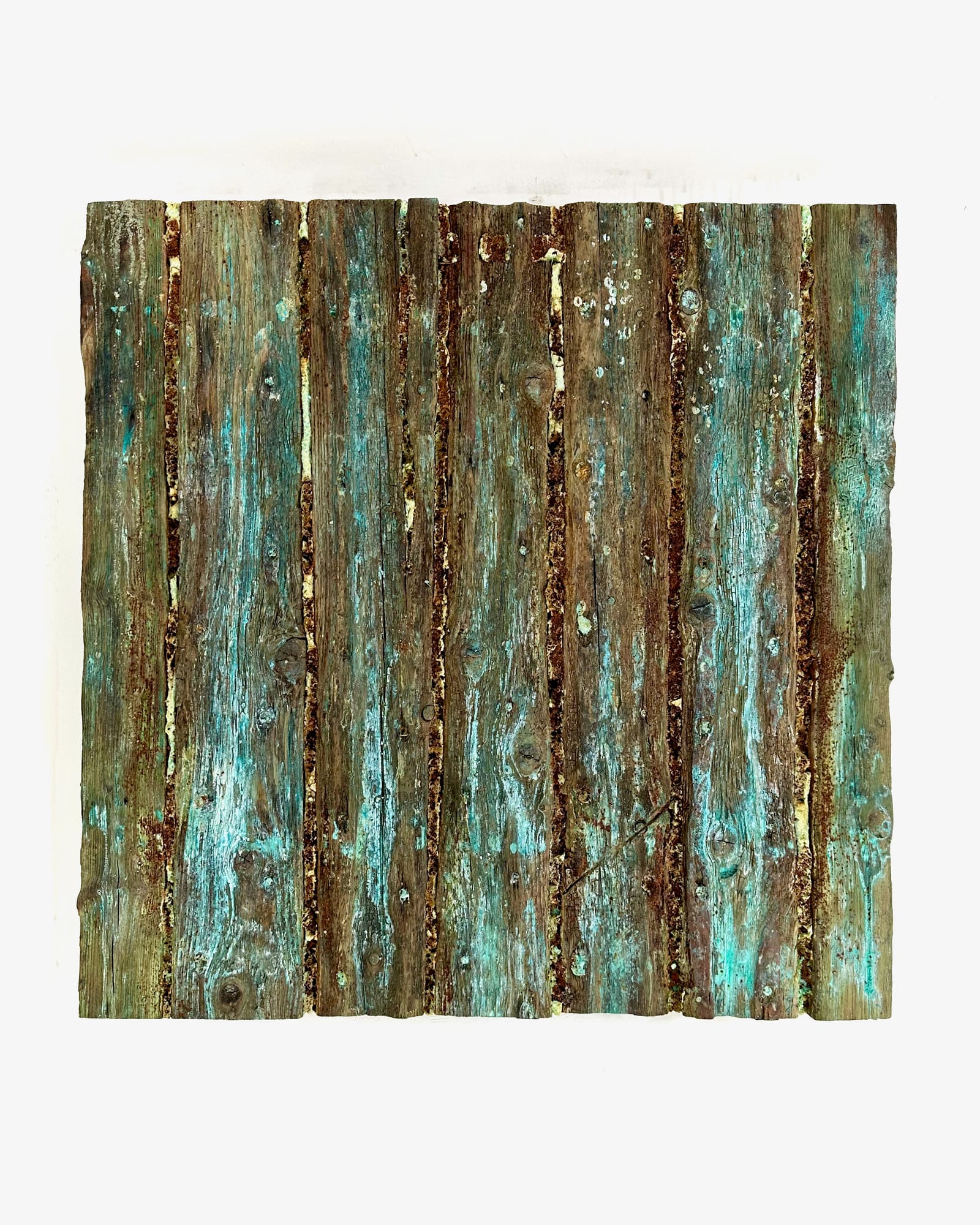

Similarily image our society designed for people—not labor and consumers—and what it might be like if one day we are actually encouraged at all levels to dream and play and invent; where the incentive structure caters for even the smallest bursts of urge to work and desire to create and there is business in constructing things so thoroughly and well thought out that they also last and stand in a hundred years.

Imagine that it is possible to make a decent living as a local tailor, because we have to pay the real costs of the clothing we otherwise freely brought home from the other side of the globe, which now at one stroke is pricelessly expensive.

Imagine that it is actually possible to make a living repairing bicycles in a small cozy workshop on the harbour.

Imagine your own sourdough bread, baked with strange, local grains not only better, but also cheaper than factory-made bakeoff, where all ingredients must be wheeled back and forth across the continent in trucks.

Imagine it teeming with small kitchens, where passionate people make takeaway from scratch and you can just sit down at a long table—and where the people already sitting there just move together and welcome you.

Imagine that picking the North Sea prawns in Morocco, just to drive them back to Northern Europe is as expensive and difficult as it sounds absurd and that our livestock must live on local crops, because the idea of clearing rainforests in South America and shipping the soy halfway around the Earth is as expensive as it is against every principle of sustainability.

In fact, imagine that the price of modern, industrial agriculture and the accompanying and even more insane plant protection reflects the environmental consequences one for one.

Imagine that genetic modification is punishable to the same degree as infringements of patent law and infringements of commercial manufacturers' copyrights are today.

Imagine that the price of electronics and plastic is in proportion to the permanent scars that mining and oil extraction leave on the planet; that the oil companies must plant one hectare of forest for every barrel of oil they pump up from the underground and that the mining companies must invest half of their profits in social projects where they recruit their workforce.

Imagine that the competition parameter par excellence is to use the least possible energy, and leave the least possible impact on the planet—and no—not just based on something as eccentrically old-fashioned as ethics and morality, but simply because that's how we've chosen to configure the economy and it's what pays off best in both the short and long term.

And while you're still letting your imagination run wild just think how nice it would be if you weren't always so fucking busy and always and forever was staring at your mobile; that you were able to treat yourself to some creative downtime, sleep like a baby at night, and wake up both well-rested and ready for a beautiful, new day, with lots of eureka moments and open possibilities.

—in fact, everything that is included when you imagine paradise life on a secluded tropical island—just here, at home where the seasons change and we know and love each other and each other's more or less pronounced quirks.

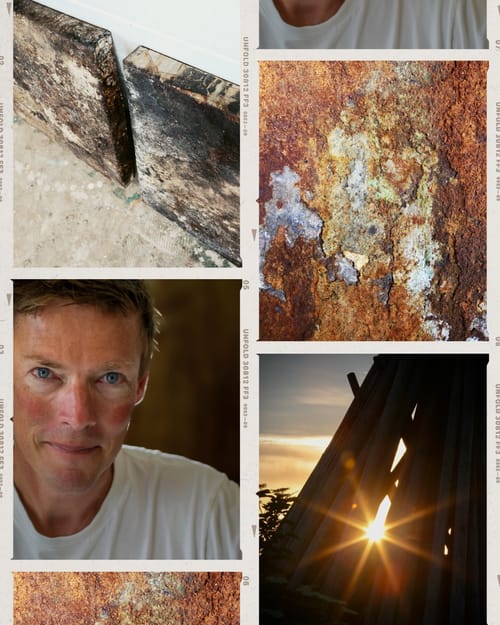

I would love that way of living—hands-on—not least because what needs change in our modern, detached everyday life is anything but our lovely neighbours, the horizon and the sea.

The column was originally published in Dagbladet Ringkøbing-Skjern back in April 2020.